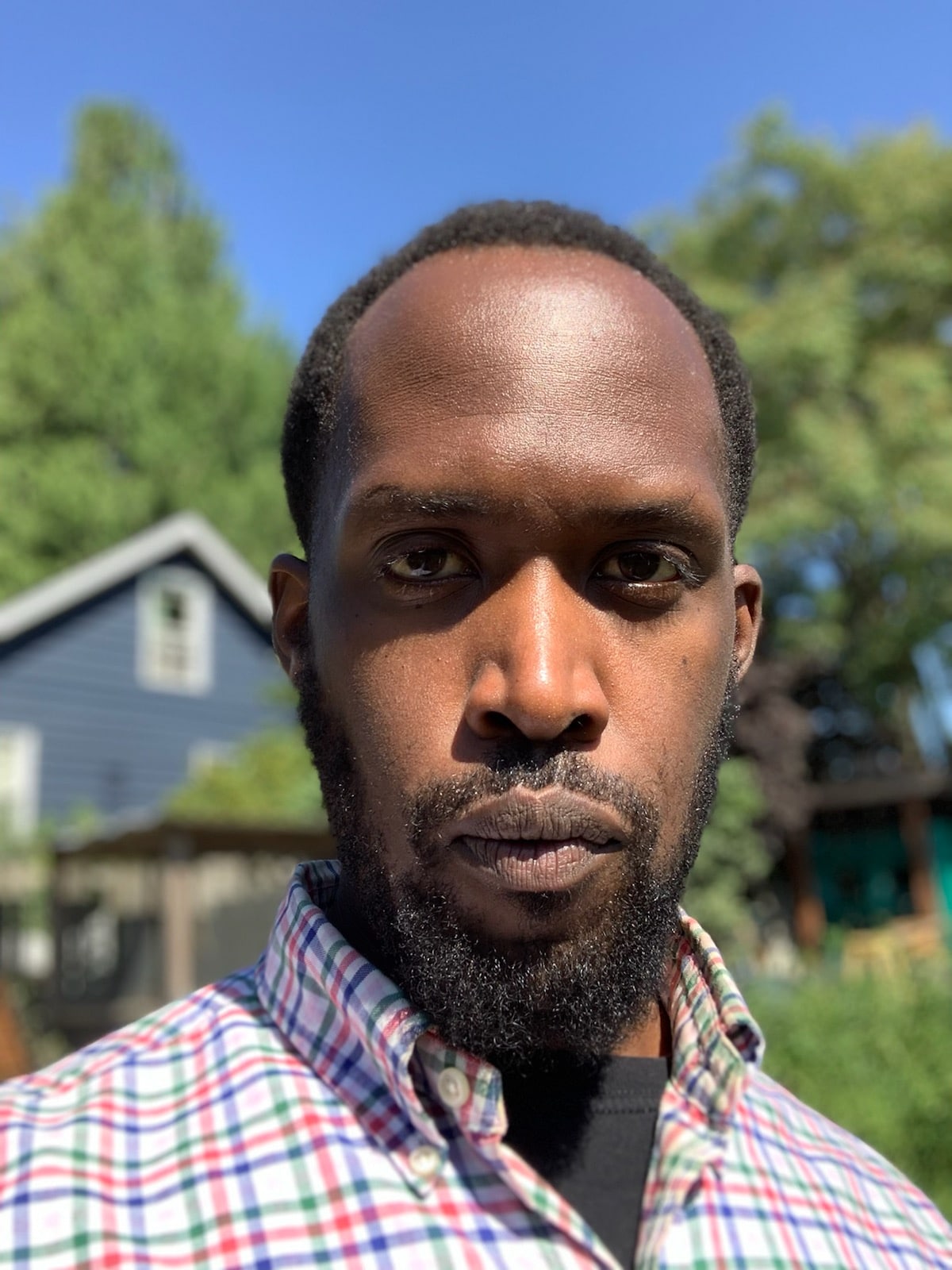

Holding Space: Njuguna Gishuru

Family history – First African import store in Pike Place

My father, Peter Gisharu, is the longest residing Kenyan immigrant in Seattle.

My father, Peter Gisharu, is the longest residing Kenyan immigrant in Seattle. He came to the United States in 1963 through the Tom Mboya airlifts. In the early 60s, African students and students from abroad were first allowed to go to school in the United States.

My father was a part of the original group that came to the Central District where black folks were; we lived with a family in the Central District and another family in Montlake. Eventually, he went to Seattle University and decided to reside in Seattle. In those days, most African students were going back to their country of origin, as many countries in Africa were becoming independent, to be leaders, ministers, business leaders, etc…

My mother came to the United States in the late 70s, from London, after being there for school. My parents are from the group in the Kenyan community who welcomed others and brought others to Seattle and established community institutions and community groups, like many other African and immigrant groups.

When people from your country come here, it’s common to host them in your homes; you direct them to housing and job opportunities. My parents were people that were here earlier than anybody else, for the most part. When I was growing up in the 80/and the 90s, our communities primarily lived in the Southend, and some in the Central District, but people were moving south.

My parents owned an African import store; they were one of the first, if not our store was one of the first African import stores in Pike Place Market and one of the most successful. This business showed others in our communities that you can make a business from African imports. They did that for about 20 years.

My mother is also a community organizer who does community leadership development primarily for immigrant women, African immigrants, and other groups. My father runs the African Chamber of Commerce, which started in 1999 to promote trade and investment between the US and Africa and promote small business development in African communities. My parents are longtime community leaders, well known in the community, and folks that have been around for a long time.

Growing up in South Seattle

I’m an original Southend guy who has seen Seattle change from the 80s when I was a small child, growing up in the 90s, and then to now.

My experience growing up in the Rainier Valley was very positive; I lived a regular kid life. I rode a bike a lot and journeyed throughout the Southend – Beacon Hill, Rainer Vista, Holly Park, Rainier Beach, and Skyway. As a teen, there were a lot of late nights events at community centers to have safe spaces for youth to meet at night.

I witnessed violence that I had to navigate as a kid, but it wasn’t anything I found unusu al; it’s just something you deal with. I spent a lot of time going to parks and community centers and exploring different parts of the Southend to visit friends. I enjoyed growing up in the Southend, going to the Rainier Valley Community Center and Rainier Beach Community Center to play basketball & football, and going to different parks. Even though there could be danger in some parks due to gang activity. You have to navigate these situations, and sometimes we know those people, so we’re good. I remember going to various apartment complexes like the Empire Way apartments, different neighborhoods like Rainer Vista, Holly Park, other public housing, and places where we had family members.

al; it’s just something you deal with. I spent a lot of time going to parks and community centers and exploring different parts of the Southend to visit friends. I enjoyed growing up in the Southend, going to the Rainier Valley Community Center and Rainier Beach Community Center to play basketball & football, and going to different parks. Even though there could be danger in some parks due to gang activity. You have to navigate these situations, and sometimes we know those people, so we’re good. I remember going to various apartment complexes like the Empire Way apartments, different neighborhoods like Rainer Vista, Holly Park, other public housing, and places where we had family members.

I always felt like a Rainier Beach/Soufend person who knows the area; it’s just our neighbor(hood). You know, who is who, you know, the good, the bad, everything it’s home;

It’s hard to find a single incident where I felt a sense of community because I spent most of my life as a young person before I went to college in the Southend primarily. I always felt a sense of community; In high school, I used to work at Rainier Beach library, and everybody from the neighborhood would come in. I always felt like a Rainier Beach/Soufend person who knows the area; it’s just our neighbor(hood). You know, who is who, you know, the good, the bad, everything it’s home; I always felt a sense of community in that way.

I never felt unsafe, personally, in the Southend ever because it’s my neighborhood. The danger was somewhat normalized; I didn’t feel like I was a target. Growing up in this neighborhood, I learned how to navigate situations; I always feel a sense of community in the Southend, and it’s the place I feel most comfortable, probably on, on the planet. I can walk down random streets; I know these streets from growing up, and I still know the Southend.

When I came back to Seattle as a young adult, I spent a lot of time at Cafe Avole with Solomon and Gavin. We definitely had a deep sense of community in that space on Holly & Rainier; unfortunately, that business has been displaced. That’s probably the last place I felt a sense of community in the same way in the neighborhood. Looking at the area over the past year and a half, two years, you can see the physical changes.

Redlining in Seattle

Connecting the current housing and displacement crisis to the past housing policies and redlining practices prevented people, primarily people of color, in the Central District and the Southend from accessing the value in their homes, getting loans, and building value in their homes for a long time. Which didn’t allow us to build up the wealth that white folks and people north of the 90 could build. We weren’t able to create economic stability to retain our homes.

I think the issue is the local community was taken out of the major industry jobs and then, due to redlining, didn’t build equity in their homes, and then our homes became low value.

I mean, there were other economic forces; when I was growing up, many black people worked for Boeing, and that’s how they got houses in the Rainier Valley and South Seattle. This is a non-existent reality now, but growing up, it was normal for black people to work for major employers; now, the major employers don’t include us. Some companies are now hiring more black folks in this economy, but they usually come from outside of the Seattle metropolitan area. Which is excellent; I have moved to other places, too. I think the issue is the local community was taken out of the major industry jobs and then, due to redlining, didn’t build equity in their homes, and then our homes became low value.

In this environment, because other people have wealth, access to capital, and have been empowered by the system, they can take advantage of what was done through redlining in the Southend, which advances gentrification. I think redlining created this current situation or was one of the major factors.

I want to have affordable housing that meets our needs and allows us to build wealth and live in a community with a sound school system, safety systems, police systems, and community systems that meet our needs. Often, what causes displacement is that we find better opportunities for our families in better environments in different places. I want our communities to also be there around us (BIPOC), not just individually. Also, the systems around us should be supportive and up to par, particularly the school system. It’s not just the home but the school system around children and their environment. When you have to balance everything, the cost of the housing, where it’s located, schools, proximity to family and friends, I feel like living in the Southend has everything covered to a degree.

Economy Economies

Economic empowerment is critical; opportunities should be focused on giving communities control of their economic power in terms of the money and the value generated by people’s presence. For example, communities own food systems and have stores that sell fresh foods. Another example is having access to local health care facilities like childbirth and childcare, which are essential to serving our communities needs.

Funding usually goes elsewhere; I think there are opportunities for shifting that money in the Southend to communities to generate wealth and value in ways that anchor them in the community. I’ve witnessed the Rainier Valley Midwives build a new birthing center and make efforts to train more midwives from communities of color. There’s money, and there’s knowledge in our communities about how to birth babies. We have communities of people that have given birth to children, in refugee camps, in their homes; they have cultural knowledge that I think we can translate into the system here and bring more money into our communities.

We need systems that define the value already in the community, ensure it remains in the community, and get funding to institutions that employ community members.

There need to be intentional strategies to find where we can transfer power through control of our community economies to our people, so they can be rooted in the Southend. If they’re more midwives making living wages because they’re part of institutions that can get that public money, to bring community members in to have their babies in a healthy, natural way. They can live in the Southend, and they can afford to live there. They’re serving their communities, building the foundation of a health care system. Those folks can create relationships where the mothers and families can now come back to their health care providers.

We need systems that define the value already in the community, ensure it remains in the community, and get funding to institutions that employ community members. This will allow opportunities to build income and wealth, and then they can stay in the community because they have economic power.

I don’t personally feel that the approach to only building affordable housing will be sustainable because people’s lives, ultimately, the factors of life will take even if you qualify for affordable housing, it will probably take you outside of the city.

Currently, the strategy is to create a lot of affordable housing; this makes a two-class city with people who can afford to live in Seattle. That’s the compromise that local government is making, and to me, that’s not the answer. They’re trying to accommodate everyone by providing ample affordable housing, but it’s not a sustainable solution, especially when thinking about growing families. While building more affordable housing, the economic component needs to be ramped up tremendously. It goes beyond small business development because small businesses don’t usually employ many people outside of their owners. We need to look at more strategies for building local economies that hire many people to anchor local communities. I don’t personally feel that the approach to only building affordable housing will be sustainable because people’s lives, ultimately, the factors of life will take even if you qualify for affordable housing, it will probably take you outside of the city.