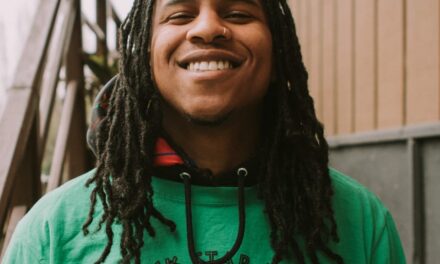

Holding Space: Gregory Davis

My connection to Rainier Valley goes all the way back to my college days at Seattle U. I remember being in my freshman year, sticking my head out the window and seeing Mt. Rainier, and there was this street that seemed to just go straight there — which ended up being Rainier Avenue. So I asked my roommate, “Does that road go all the way to the mountain?” and of course he’s like, “No, that’s Rainier Valley.” Never did I imagine I’d have a footprint here in the future.

At some point, my parents actually purchased a house on Beacon Hill, which is where I’ve been living since ‘85. My father was in public affairs, so I was always somehow involved in the community. Because of all that, I’ve always organized where I’ve worked, so when I moved on from the Central Area Motivation Program — now Byrd Barr Place — and started running what is now Urban Impact, that’s really when I began my Rainier Valley presence in earnest, and really started focusing more on Rainier Beach.

Eventually there came a time when the city administration wanted to do some neighborhood planning, and they started asking for folx who wanted to be involved. Now, I knew from my background that neighborhood planning is one great way to hold the city accountable to its investments in a neighborhood, and that we had to get everyone organized beforehand. So really, that’s where the story of RBAC begins — only back then it was the Rainier Beach Community Empowerment Coalition.

To combat that lack of connection to community & education, we started doing the Back2School Bash & the Town Halls. Since then we’ve hosted 18 Back2School Bashes and about 50 Town Halls.

Now, we’re one of the go-to organizations in the city. Whenever someone wants to do development in the neighborhood, we are among the first to be contacted to take a look at the project. Once the city started to notice our organizing and we started applying for funding, we dove into this research project to see if residents felt connected to the neighborhood and if our students felt connected to their schools. The unfortunate answer was that they didn’t. To combat that lack of connection to community & education, we started doing the Back2School Bash & the Town Halls. Since then we’ve hosted 18 Back2School Bashes and about 50 Town Halls.

Recently, we sent a survey to our lead team asking the question, “Does RBAC’s work prevent gentrification and displacement?” And we had one response that said ‘no,’ which really kind of took us by surprise initially, but it’s because this person had been living in the Lake Washington apartments when the rent got raised by $400 out of nowhere. This person — who was an employee of ours at that time — had asked us if we could intervene in this situation, and so you know we wrote a letter to the apartment complex owners, but nothing changed. Because of that rent increase, this RBAC employee was displaced to Sand Point. In retrospect we’re thinking: $400 a month, that’s $4,800 a year? We could’ve just paid that. As an organization that’s supposed to be fighting displacement, we should be marshalling resources from the city to go towards residents that are on the brink of being shoved out.

One way I can say we do fight displacement is by hiring young folx from the Rainier Beach neighborhood.

One way I can say we do fight displacement is by hiring young folx from the Rainier Beach neighborhood. We did this really intentionally as a way to secure some economic empowerment for them. We could have brought in adult staff to run these programs for neighborhood youth, but we said no, we want to hire them. And we saw that as an economic development strategy for the neighborhood. Now we can look at our annual budget and see that most of the money we get is going directly back into the community through our staff.

The Chief Sealth Trail project was one of those moments where I was really proud of our community. We got a grant to create a space near public transit where people could be actively involved while they waited, and we chose this area by the Light Rail station where we operated the Corner Greeters. It was a space that would always get so muddy anytime it rained, and we originally wanted to do a terraced garden, but ended up paving it and putting in 3 raised garden beds. There were a lot of processes and red tape we had to go through to make it happen, but we made it happen. We were just so proud to finally have a beautiful space in our own neighborhood– something that we made out of nothing– that was ours ours, and that served the purpose of food justice & community safety. We ended up calling it ‘Project Reclaim.’ When it was all finished, we took a picture of it and it just looked so pristine, like something you could really have pride in. And it was visible proof that we could take resources from the city and give it back to the neighborhood in a useful way.

Having neighborhood anchors that aren’t constantly under threat of being uprooted would mean everything to me.

Having neighborhood anchors that aren’t constantly under threat of being uprooted would mean everything to me. It would contribute to the proof that us Black and Indigenous folx know what our needs are and that there’s no reason for people to continuously second guess us. Black-led and indigenous organizations are currently underinvested in because we’re constantly second-guessed about whether we know what we’re doing when our ideas don’t match what someone else thinks we should be doing.

Early on, we were holding RBAC planning meetings inside what was the Rainier Beach Food and Farm Hub, in a space that was about the size of a bathroom. Now we’re renting a decent sized office space, and just purchased our own parcel right across the street from the Rainier Beach Light Rail Station. Even though we own that space and that building, we still have to work hard to make sure that we continue disrupting gentrification in this area. So I wouldn’t say the threat of RBAC being displaced has been incredibly diminished, because we’re still at risk, but we are in the way. Especially when it comes to our YATTAs [Young Adults Transitioning To Adulthood], who aren’t pullin’ no punches. They’ve got no qualms about fighting for what’s theirs, and that’s why we’ve got to do whatever it takes to make sure our youth see Rainier Beach as theirs, see it as something to fight for.