Make Your Voice Heard!

The Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan is 12 years old – and it’s time for an update. The plan identifies actions that the community and the City should take to make your neighborhood a better place. You are the experts and your ideas will direct the work to update this important plan over the next year.

Please join the us at the first of four meetings to shape the future of the Rainier Beach Urban Village. This meeting will establish the community’s priorities that will influence zoning, city services, and transportation planning.

DETAILS:

- Event: Community-wide Meeting

- Date: Sat., March 19, 2011

- Time: 9:00 a.m. – Noon: Community Meeting; Noon – 1:00 p.m. Open House

- Location: South Shore K-8 School (4800 S. Henderson Street Seattle, WA 98118)

Can’t come? Learn more, sign up for e-mail alerts, and fill out a survey from the Rainier Beach Neighborhood Plan Update site.

Help get the word out by printing and distributing the event announcement:

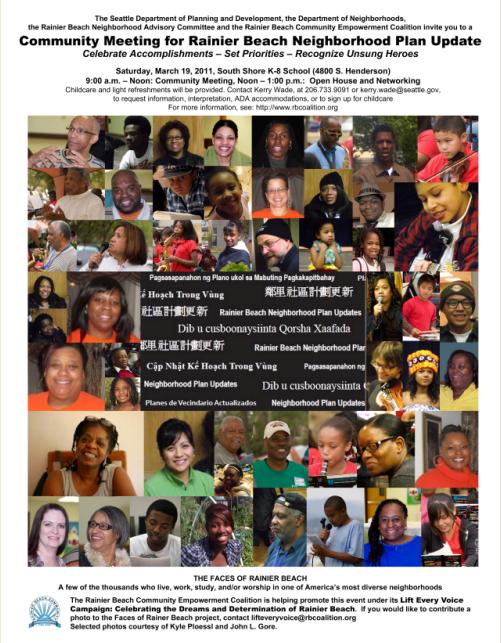

RB March 19 Invitation web

OR Click March 19 Event Flyer to download flyer pictured at right.

NOTE:

Elements of the annual Town Hall Meeting sponsored by the Rainier Beach Community Empowerment Coalition at the beginning of each year are being combined with the Community-wide Event.

Organizations that serve the Rainier Beach area are invited to participate in this survey to share victories from 2010, identify priorities for 2011, and nominate individuals and organizations for the annual RB Unsung Hero Awards.

Can I Get a Witness?

Mt. Zion’s Flame-Throwing New Preacher Has Been Telling Seattle’s Black Middle Class Exactly What They Don’t Want to Hear. PHOTOS BY ANNIE MARIE MUSSELMAN

by Phil Campbell

Mt. Zion’s youth choir has just finished a transcendent rendition of “I Will Rejoice.” The echo still hangs in the air as Rev. Leslie Braxton takes the pulpit. He quickly sours the jubilant mood. “There are some of us in here today,” the minister intones, “so dressed up, so well educated, so comfortable, living so high on the hog. But you have lived for yourself. You have lived by yourself. And you have an ‘I’ problem — an I, me, and my [problem] so badly that you are not fit to live in your selfish, isolated pursuit of your own promised land.”

The middle- to upper-middle-class blacks who are present hold back the usual hail of “amens,” leaving only Braxton’s voice to fill the interior of Mt. Zion’s sanctuary. In a black church, the quiet can only be interpreted as disagreement or general discomfort. The only parishioner who seems to be appreciating Braxton’s diatribe is a man who, at least judging from his attire, doesn’t fit into the tax bracket Braxton is targeting. He claps loudly and laughs as the reverend relentlessly chastises the wealthier people present.

At the podium, Braxton has two basic expressions. The first is a sort of cherubic joy, as if he were learning new, incredible things from the words coming out of his own mouth. The second expression is that of a firebrand. Eyes sharp and piercing, goatee jutting out, he talks as if he could smite his darkest enemy with rhetoric alone. Right now, his face is contorted by the latter expression. “We don’t have a vision,” he declares loudly, “a standard that we’re reaching for as a people, and as a result we have given ourselves over to individualistic pursuits. A cruise. A mink coat. A house in the suburbs. A second mortgage. All of these things that may have their place, but that are not worthy of one living for them. They are a means to an end, and not an end unto themselves. We’ve given ourselves over to narcissistic living.”

These aren’t typical “black preacher” issues, the bread-and-butter topics African American ministers frequently use to stir up a crowd. The usual topics include the oppressive nature of discrimination, the callousness of Republicans, the crushing effects of poverty, the latest miscarriages of justice, and the importance of the family. Instead, Braxton is indicting his own congregation and many others in the black community, a community that is undergoing radical change during these booming economic years — not all of them for the good.

The Central District church’s first new pastor in decades, Braxton is being hailed by the media and black leaders as a young, activist minister — one who promises to turn Seattle and the local black community on its head. When he took over at Mt. Zion six months ago (he was formally installed last week), The Seattle Times ran a story lauding the Tacoma native as a “full-bore activist.” Braxton told the Times that he was looking to meld church and state in order to solve social problems: “Martin Luther King said what I believe. ‘Any religion that pretends to be concerned about the souls of men but is not concerned about the slums that damn them, not concerned about the economic conditions that strangle them, and the social conditions that cripple them, is a dry-as-dust religion.'”

But it’s unclear how much Braxton can actually accomplish, given that the congregation at Mt. Zion, and indeed a growing portion of Seattle’s black community, has become more affluent and comfortable. It’s undeniable that he wields a lot of political power as head of the largest black church in the city, one that is bedrocked in the history and principles of the local civil rights struggle. But how does he intend to use that power? It’s early in his tenure, but his first major project so far has been decidedly non-political: a multi-million dollar expansion of the church.

THE DILEMMA

“It’s hard to argue [religion] around here,” Braxton says over breakfast at the Komfort Kitchen on 23rd and Jackson. “There’s a secular, bordering-on-agnostic framework, so it becomes harder to challenge people, to make moral appeals, to challenge the ethics of people because they have no basis for it other than self-interest.”

The morning Braxton and I meet, the reverend bounds in the door, all energy, clutching an organizer in a leather case. He’s dressed in a dark Adidas track suit, the kind of clothing that, on a black man, attracts the attention of store security guards (even at 38, the minister, with the build of a football player, gets followed around in department stores). His face is naturally animated, giving him an extroverted demeanor. He strikes you as someone who can expound on any topic that comes up, and he confirms that impression with thorough, thoughtful responses to questions. Not surprisingly, his ideas are frequently laced with Biblical metaphors.

I ask about his sermon on materialism. Normally, there is a tacit understanding between pastor and congregation — a collusion of sorts. The minister can chide, coax, admonish, and uplift, but he or she cannot indict. If there is an enemy, it is an external one, like the devil, Reaganomics, or the moral decline of American society. It doesn’t do any good to take swipes at your own congregation, primarily because the minister needs the church more than the church needs the minister. If the pastor presses an attack too hard and for too long, the spiritual becomes political, and then personal. Soon, the minister finds himself or herself preaching out on the street instead of inside the temple.

A good preacher always challenges his congregation, Braxton says. “The Word of God comforts the people, but it also indicts them. It is a two-edged sword.” In days gone by, talking about greed to a black congregation would have meant attacking an external enemy (namely whites); but these days, the so-called enemy is much closer to home. One look at Mt. Zion proves that.

The predominately black congregation boasts 3,000-plus members, with an annual income of $1 million or more, making it by far the largest and richest black church in Seattle. Many of its members aren’t poor, as evidenced by the Lexuses, Mercedes, and SUVs that fill its parking lot every Sunday. There are fancy cars outside and fancy people inside: doctors, bankers, lawyers, government employees, and politicians — including King County Executive Ron Sims. Statistics show that economic times have never been better for America — including, for once, black America. While no one is saying that the pie is now divided equally, the success of many of Mt. Zion’s parishioners underscores that African Americans are getting bigger and better pieces.

This poses an interesting dilemma for pastor and parishioners alike, as Christian ideas about wealth and African American ideals about community butt right up against American dreams of independence and material success. And Braxton — who grew up welfare-dependent, but is now firmly middle class — is one of a generation of new black preachers who has to deal with it.

It takes another African American minister to see this intrinsic quandary. I read verbatim excerpts of Braxton’s sermon to Robert Jeffrey, the pastor of New Hope Baptist Church in the Central District. He is stunned. “He got away with that at Mt. Zion?” Jeffrey asks incredulously. Jeffrey’s predominately black congregation is not as affluent as Mt. Zion’s. He starts laughing. “Pretty brave guy. I don’t think I would have said that at Mt. Zion. But it’s true. It’s true. And it’s probably something they haven’t heard in a while.”

The New Testament has a lot to say about money, most of it negative. John the Baptist paved the way for the Messiah by living like a hermit in the desert and eating bugs. Jesus, also a fan of fasting and deserts, once told a rich man to give away all he had and follow Him. When the rich man refused, Jesus declared that the wealthy are about as likely to get into heaven as a camel is to pass through the eye of a needle. Does this mean Braxton and his congregation will be turned away at the pearly gates?

Braxton is annoyed at the question. Blacks don’t have to be poor to be good Christians, he says. Besides, that’s not how he reads the New Testament. “Jesus said, ‘Blest are the poor in spirit. Theirs is the kingdom of God,'” Braxton points out. “That meant, blessed are those who are in solidarity with the poor. God’s spirit reigns among folks who are not necessarily poor. The last thing a poor man wants to see is another poor man.”

If this is how Braxton feels, why does he admonish his congregation for their wealth? After all, haven’t African Americans wanted what whites have had all along? Wasn’t the civil rights movement, from the beginning, an effort to gain economic equality? Braxton’s reply is notably complex and rich with spiritual meaning, and it emphasizes the community over the individual. “It’s the white church that has been so enamored and covetous that they could enslave blacks, exterminate Native Americans, and back every evil legislation that destroyed human beings, in their pursuit of land and property and possession and profit margin, while they manipulate their theology to justify it,” the minister says. “We don’t want to take on those same evils. We always want to fight for justice and not ‘just us.’ So the black church goes through the same moral struggles as the white church. Israel [from the Old Testament] always got in trouble whenever she became comfortable. Idols of expedience. Idols of materialism. Idols of tribalism. Comfort would set in, and then, internally, she would fall apart. Then her external enemies would come and take over.”

“This raises the spiritual question raised in the Book of Judges,” he adds. “Can we be blest and still stay focused?”

HISTORY LESSONS

To put these issues into context, you have to appreciate the role Mt. Zion has historically played in the black community in Seattle, as well as what kind of authority it wields today. That story begins with Braxton’s predecessor, the legendary Rev. Samuel Berry McKinney.

When McKinney took over at Mt. Zion in 1958, there was open discrimination in housing. Labor unions all across the city were barring blacks from joining and rising in their ranks. Schools were segregated. Downtown businesses refused to hire minorities. It wasn’t the South, with Birmingham’s Bull Conner and his police dogs, but it was racism, and it could get just as ugly here as anywhere else. “I came and ran into some situations early on,” says 73-year-old McKinney, a former classmate of Martin Luther King Jr. “I had difficulty finding a house. We ran into all types of discrimination, and I was considered a troublemaker by some people because I wouldn’t sit down and take it.”

McKinney joined forces with several other key African Americans, including Rev. John H. Adams of the Central District’s First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and Edwin Pratt of the Urban League, to form a coalition of leaders fighting for civil rights. Mt. Zion was a natural anchor for the movement. It boasted a large meeting hall — a place where ideas could be shared, conflicts could be resolved, and strategies could be hammered out. Given that the church was already 70 years old at that point, it also boasted a large and established following.

In those days, rallies would start at Mt. Zion. Protesters would move on to meet more protesters at First AME, a couple blocks away, and together they would proceed downtown. Others would join in along the way until the crowds swelled, sometimes into the thousands. The target would be a department store that refused to hire minority clerks, or city hall, to protest housing discrimination or school segregation. From 1961 to 1974, there were so many protests, meetings, and organized demonstrations in Seattle that the old-guard generation of blacks, when called upon to recount one in particular, isn’t sure where to begin. “We had lots of meetings and press conferences,” says 61-year-old Constance Bown, who still attends Mt. Zion. “It’s hard to recall one specific thing.”

McKinney wasn’t a firebrand, say those who’ve worked with him. He was effective because he was a consensus-builder, someone who could work the phones and organize protests. His colleagues talk of his courage, his incredible rapport with the black community, and the kind of clout he wielded. “A lot of churches wouldn’t get involved,” recalls Charles V. Johnson, a retired judge and former head of the NAACP. “But McKinney was out front, and so his congregation was an important part of the civil rights movement.”

Of course, there were those who felt that McKinney wasn’t forceful enough. In 1975, King County Council Member Larry Gossett, then a radical activist, tried to challenge the preacher openly. When Mt. Zion was building its sanctuary at 19th and Madison, Gossett and a few others intimidated white construction workers into fleeing the job site. Why? He didn’t believe the church was trying hard enough to recruit black workers. Gossett felt firsthand the respect that McKinney garnered. “[Our protest] lasted one day,” he says. “I never got so much heat from the black community. We had to apologize. All of our supporters said, ‘Don’t be attacking Rev. McKinney.’ They thought we were wrong.”

THE PREACHER, THE PROBLEMS

At 54, Gossett’s approach to politics has softened a bit, but his respect for Mt. Zion and the power its pastor holds has not. What Samuel McKinney created, Leslie Braxton has now taken over. “Just by the nature of the position that [Braxton] has, it automatically makes him a leader, rightly or wrongly,” Gossett says. “The mantle of leadership goes to him.”

Braxton is slowly picking up that role. The most overtly political appearance he’s made so far was on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday last month. Braxton’s photo appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and showed him marching alongside Rev. John Hunter, the new minister of First AME, during a rally. The appearance with Hunter sent a strong message to many in the black community. These two ministers — who are both young, energetic, and new to their positions — comprise the new spiritual leadership of black Seattle. But will they cast a legacy as long as their predecessors did? Perhaps more importantly, do the times we live in make that kind of legacy-building possible?

Seattle is a city of tremendous class division. The .com economy has pushed many incomes skyward: There are more millionaires per capita here than in any other city in America. At the same time, political decisions at the state level have made Washington the eighth worst state in the country when it comes to feeding the hungry. Moreover, Seattle’s neighborhoods are well known and well marked. The rich (and mostly white) live in Laurelhurst and Broadmoor. The middle class can be found in neighborhoods like Wallingford and West Seattle. The working class and poor (and disproportionately minority) live south of Madison Avenue, from the Central District down to Rainier Valley.

The city’s booming economy is having a dramatic effect on African Americans in particular. Some black families are moving up and out of the traditionally black Central District into posher areas like Kirkland, Newport Hills, and Mercer Island. At the same time, poorer blacks — victims of rising property taxes and ballooning housing prices — are being forced out of Seattle. The Central District is being gentrified at an unbelievable rate: In another 10 years, it may be just another predominately white, upper-middle-class neighborhood.

Race relations are still a problem in Seattle. Local African Americans — who make up 10 percent of the city’s population, according to the last census — are given harsher treatment by the courts. Two recent studies found that bails are set higher for minority defendants in Washington state, and that King County prosecutors file stiffer charges against minorities than whites. Critics also charge that the “civility” laws pushed through the Seattle City Council by City Attorney Mark Sidran, especially the parks exclusion ban and the automobile impound ordinance (which makes it easier to impound cars), target minorities. According to an ACLU study, 47 percent of those banned from city parks for a year were racial minorities. And according to an investigation by The Seattle Times, blacks are six times more likely than whites to have their cars taken under the impound ordinance.

The Seattle Police Department is another source of problems. More than 200 people showed up for a hearing last June to address police mistreatment of minorities. Many of them testified that they had been physically abused or pulled over for “Driving While Black.” During the WTO protests in December, the police pulled black City Council Member Richard McIver from his car, even after he’d showed them identification. “There are huge flaws with the officers when it comes to people of color,” McIver said a day later. “I’m 58 years old. I had on a $400 suit, but last night I was just another nigger.”

REDEFINING ROLES

So does Braxton see a role for Mt. Zion in fighting these battles? Think about it. If Braxton persuaded a mere fraction of his congregation to kick into direct political action, he could storm city hall and demand a repeal of the automobile-impound ordinance or the parks ban. Or he could call much-needed attention to the impact of the city’s skyrocketing property values. It could be a brilliantly coordinated media spectacle, and it would shock the hell out of everybody.

Pressed on the issue, Braxton gives a response that seems at odds with his earlier statements to the dailies about politics and activism. These are different, more pessimistic times, he says. “During the 1960s and ’70s, there was a movement across the country. The climate was there.” But now, says Braxton, “the only thing that seems to get people motivated is the reduction of their tax liability. You don’t have any driving issues that motivate people that way. The black middle class is caught in the same kind of classist indifference as the white middle class. And the black underclass is caught up in despair. It’s very hard to focus people on an agenda.”

He says that “raising the issue from the pulpit, encouraging people to become involved,” and influencing the powerful members of his congregation (like Ron Sims) is his proper role. Some members of the Mt. Zion congregation agree. Braxton will do what the Lord wills him to do, says Elma Horton, who has been with the church for 15 years. Dawn Mason, a former state legislator and member of Mt. Zion, adds, “I would hope that this city and community does not look to him as this person who will speak to everything. He is a spiritual leader. He will not be everything for all people.”

We can gain some insight into what Braxton will likely do in the years ahead by looking at what he accomplished as pastor for 12 years at the First Shiloh Baptist Church in Buffalo, New York. While he was there, he concentrated on expanding the church (it grew from 225 to 967 members during his tenure). He established a non-profit housing development corporation, which he used to help rebuild the inner-city neighborhood that surrounded the church. Taking on youth issues, Braxton established programs to keep kids out of gangs, and also founded a small Baptist high school in 1998.

Braxton confirms that his long-term plans for Seattle are similar. He’ll continue the programs Mt. Zion already runs, such as its housing development corporation and its feed-the-needy program. He’ll also work with African American youth. What he’s most excited about, though, is his plan to spearhead the church’s fourth major expansion. On a moderately sized lot on 20th Avenue, Mt. Zion wants to build a Family Life Center, which will house all of the church’s family and outreach programs, including literacy and GED classes. Braxton is also launching a youth and outreach foundation that will specifically target young African Americans. The “outreach” arm of the foundation is aimed at tackling chronic social problems such as drug addiction.

In Seattle, as in Buffalo, Braxton wants his congregation to grow. In fact, the ambitious reverend wants Mt. Zion to become a regional mega-church. Right now, if he tests the limits of Seattle’s fire codes, he can get 900 people into the sanctuary; he wants a sanctuary that will seat 1,600 comfortably. He also wants more administrative office space and a multi-tiered garage. “We’re out of room and we’re growing every week,” Braxton says, the pride evident in his voice. “We’re probably six to eight months away from any hard numbers, but looking at the scope of it, it could be $10 million, probably $12 to $15 million. Why don’t you just call it a ‘multi-million dollar project?'”

Times have changed, obviously. The large-scale social work of Mt. Zion today has squarely replaced the organized political activity of the previous generation. Where McKinney once called for rallies to take over downtown Seattle, Braxton now hopes to build a literacy center that draws people to the Central District. Where issues of discrimination were once met with signs, meetings, and impassioned speeches, the impassioned speeches now are reserved for the pulpit.

You might expect McKinney, a political veteran, to lament the change in focus. But when asked what he considers the most important issue facing Braxton and Mt. Zion, he pauses and then says dramatically, parking. “The church is growing,” McKinney explains. “Where the church is located, it’s hemmed in. When we say that people come to church, [we say] it’s for the choirs, the sermons, and all that. But they also want to know, ‘Where can I park my car?’ The churches that have the space to park their cars are the ones that can grow.” But what about Braxton’s complaint that much of the black community has become too comfortable? Isn’t that an important issue? McKinney pauses again. The reverend certainly has a dramatic sense for pauses. “We lack a vision,” he says flatly. “Tell me. Did [Braxton] propose one?”

When it comes to the few battles Braxton has picked so far, he’s taken surprising positions. He didn’t see the point behind protests against the World Trade Organization, for example. While he knows that social injustice occurs in the Third World, Braxton thinks that trade is the answer, not disruptive protests. “There needed to be a trade agreement,” Braxton asserts. “There needed to be dialogue on issues like the environment and human rights. But the demonstrators prevented the dialogue from going on. Instead of being voices crying in the wilderness, we needed to be delegates speaking at the table.”

In fact, Braxton and a select few met with U.S. Transportation Secretary Rodney Slater and dozens of WTO delegates from Africa. Their goal was to foster trade. J. J. Jones, president of the local chapter of the National Black Chamber of Commerce and a member of Mt. Zion, brags that “the day [the police] were riding down the Pike Place Market, we were holding a reception at the Seattle Art Museum. We just told the police, ‘Keep those [protesters] off of us.'”

Braxton took another unexpected stance against the Speech, Hearing and Deafness Center, which was looking to build a 170-unit apartment building near Mt. Zion for people with below-median incomes. Braxton says he opposed the project on the grounds that it was bad for the poor. “We are against warehousing poor people,” he says. “That creates poverty. And you can’t just put poor, real poor, and real, real poor together. It does no benefit to the poor, and it does no benefit to the community.” Braxton, who expressed his concerns during a meeting with the center, had other problems with the project. For example, he says the center’s plans don’t include a play area for the children who might live there.

But critics say Braxton’s analysis doesn’t hold water. The center would offer apartments for folks who make 30 percent, 40 percent, 60 percent, and 80 percent of median income. Low-income housing advocate John Fox points out that the median income for one person in the city (with its hyper-inflated economy) is $43,820. That means that someone making $26,292 is making 60 percent of the median. While that may not fit today’s middle-class standards, it’s not poor, either. Besides, argues Fox, the Central District needs to begin building more affordable housing before gentrification runs everybody out. “Maybe he’s not familiar enough with his community yet,” he says. “The black community is just holding on by its fingertips in that area. It requires more truly affordable housing to survive.”

Braxton and other church officials gave their reluctant blessing to the project several months after the center agreed to cut the number of units from 170 to 96. They also agreed that of the 96 units, 25 would be rented at the market rate (which, notably, is only 80 percent of median income). But Edward Freedman, the center’s director, suspects Braxton’s objections were more about protecting the church than the poor. He says that at a neighborhood meeting, Braxton and a few others fretted that the people who moved in next door would become dependent on Mt. Zion for aid (Braxton denies making the comment). “I don’t know why it would fall to the church,” says Freedman, “or why it would fall to us.”

BEHIND THE PULPIT

Behind the pulpit, Braxton hits on all the right themes. He warns his congregation against putting “a third-rate governor from Texas” in the White House. He bemoans the AIDS epidemic that is now killing countless people in Africa. He slams Washington voters for passing anti-affirmative action legislation a couple years ago. He slams Washington voters again for passing I-695, a regressive tax law that is having a crushing effect on the state’s transportation budget.

But then there’s that thorny issue of greed and class division that Braxton occasionally harps on. “We’re nothing but outsides!” he yells at his flock. “Nothing but a nice hairdo. Nothing but a new suit. Nothing but a late-model car. Nothing but a nice home in the suburbs. Nothing but a slick business card…. We’ve forsaken the sacred ‘we’ [for] the demonic ‘I’ that is tearing our nation, our churches, and our families apart.”

Does Braxton offer a common vision for black Seattle? Does he offer a way to solve the problems he so passionately outlines? Well, no. In fact, about halfway through the sermon, he changes tracks. He lets his congregation off the hook. After all, as Braxton says, the word of God indicts, but it also comforts. His speech, it turns out, is not about the generation that is currently achieving a measure of financial success — that bridge generation to which he and so many parishioners belong. The sermon is about the generation that follows Braxton’s — he warns his congregation about the danger of raising “brats.”

“Many of our children have a lack of gratitude for what they have, because they have had no personal experience of struggle,” Braxton says. “Most of us in here today, if you have something, you’re the first in the family to have gotten it…. No one gave it to you.” Judging by the applause, the parishioners agree with this. “You had to get it the old-fashioned way — you earned it.” Some are on their feet now. The “amens” are floating toward heaven. “Whereas we complain about the struggle, truth be told, that’s why you are the person that you are. Because through the struggle, you came through like pure gold [applause]. And because of the struggle, you appreciate what you have [more applause]. And you take care of what you have. Reaping without sowing ruins the best of us.”

This is the crux. Braxton is leading a new black middle class, which is unsure of itself and the direction in which it is heading. What comes after wholesale segregation and poverty, when there are no more obvious battles left to keep the community together, when economic discrimination may finally become somebody else’s problem? The struggle for equality isn’t over yet, of course, but the battles are less distinct, more difficult to handle directly.

Braxton concludes his sermon with rhetoric that is not designed to restore community, but rather to bolster the individual. You can do anything, he cries, through Christ. The reverend is tired of “pity parties,” whether it’s racism, reverse racism, age-ism, sexism, or something else. “If you got Jesus, he’s more than the whole world against you,” Braxton shouts at the top of his lungs. “And if you got Jesus, I come to tell you all things are yours. All things are possible. And the joy of the Lord will be your strength. Have I got a witness?”

Everyone is on their feet now. Braxton leads the singing, and the sheer force of his passion sweeps the problems that he has just articulated away — for now.