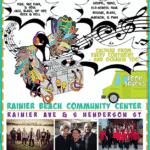

SEATTLE — Leandre Nsabi, a senior at Rainier Beach

High School here, received some bluntly practical advice from an instructor

recently. “My teacher said there’s a lot of money to be made in computer

science,” Leandre said. “It could be really helpful in the future.”

That teacher, Steven Edouard, knows a few things

about the subject. When he is not volunteering as a computer science instructor

four days a week, Mr. Edouard works at Microsoft. He is one

of 110 engineers from high-tech companies who are part of a Microsoft program

aimed at getting high school students hooked on computer science, so they go on

to pursue careers in the field.

In doing so, Microsoft is taking an unusual

approach to tackling a shortage of computer science graduates — one of the most

serious issues facing the technology industry, and a broader challenge for the

nation’s economy.

There are likely to be 150,000 computing jobs

opening up each year through 2020, according to an analysis of federal

forecasts by the Association for Computing Machinery, a professional society

for computing researchers. But despite the hoopla around start-up celebrities

like Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, fewer than 40,000 American students received

bachelor’s degrees in computer science during 2010, the National Center for

Education Statistics estimates. And the wider job market remains weak.

“People can’t get jobs, and we have jobs that can’t

be filled,” Brad Smith, Microsoft’s general counsel who oversees its

philanthropic efforts, said in a recent interview.

Big technology companies have complained for years

about a dearth of technical talent, a problem they have tried to solve by lobbying

for looser immigration rules to accommodate

more foreign engineers and sponsoring tech competitions to encourage student

interest in the industry. Google, for one, holds a programming summer camp for

incoming ninth graders and underwrites an effort called CS4HS, in which high

school teachers sharpen their computer science skills in workshops at local

universities.

But Microsoft is sending its employees to the front

lines, encouraging them to commit to teaching a high school computer science

class for a full school year. Its engineers, who earn a small stipend for their

classroom time, are in at least two hourlong classes a week and sometimes as

many as five. Schools arrange the classes for first thing in the day to avoid

interfering with the schedules of the engineers, who often do not arrive at

Microsoft until the late morning.

The program started as a grass-roots effort by

Kevin Wang, a Microsoft engineer with a master’s degree in education from

Harvard.

In 2009, he began volunteering as a computer

science teacher at a Seattle public high school on his way to work. After executives

at Microsoft caught wind of what he was doing, they put financial support

behind the effort — which is known as Technology Education and Literacy in

Schools, or Teals — and let Mr. Wang run it full time.

The program is now in 22 schools in the Seattle

area and has expanded to more than a dozen other schools in Washington, Utah,

North Dakota, California and other states this academic year. Microsoft wants

other big technology companies to back the effort so it can broaden the number

of outside engineers involved.

This year, only 19 of the 110 teachers in the

program are not Microsoft employees. In some cases, the program has thrown

together volunteers from companies that spend a lot of their time beating each

other up in the marketplace.

“I think education and bringing more people into

the field is something all technology companies agree on,” said Alyssa Caulley,

a Google software engineer, who, along with a Microsoft volunteer, is teaching

a computer science class at Woodside High School in Woodside, Calif.

While computer science can be an intimidating

subject, Microsoft has sought to connect it to the technologies most students

use in their everyday lives. At Rainier Beach High recently, Peli de Halleux, a

Microsoft software engineer, taught a class on making software for mobile

phones.

The students buried their faces in the phones,

supplied by Microsoft. They were asked to create programs that performed simple

functions, like playing a random song when the phones were shaken.